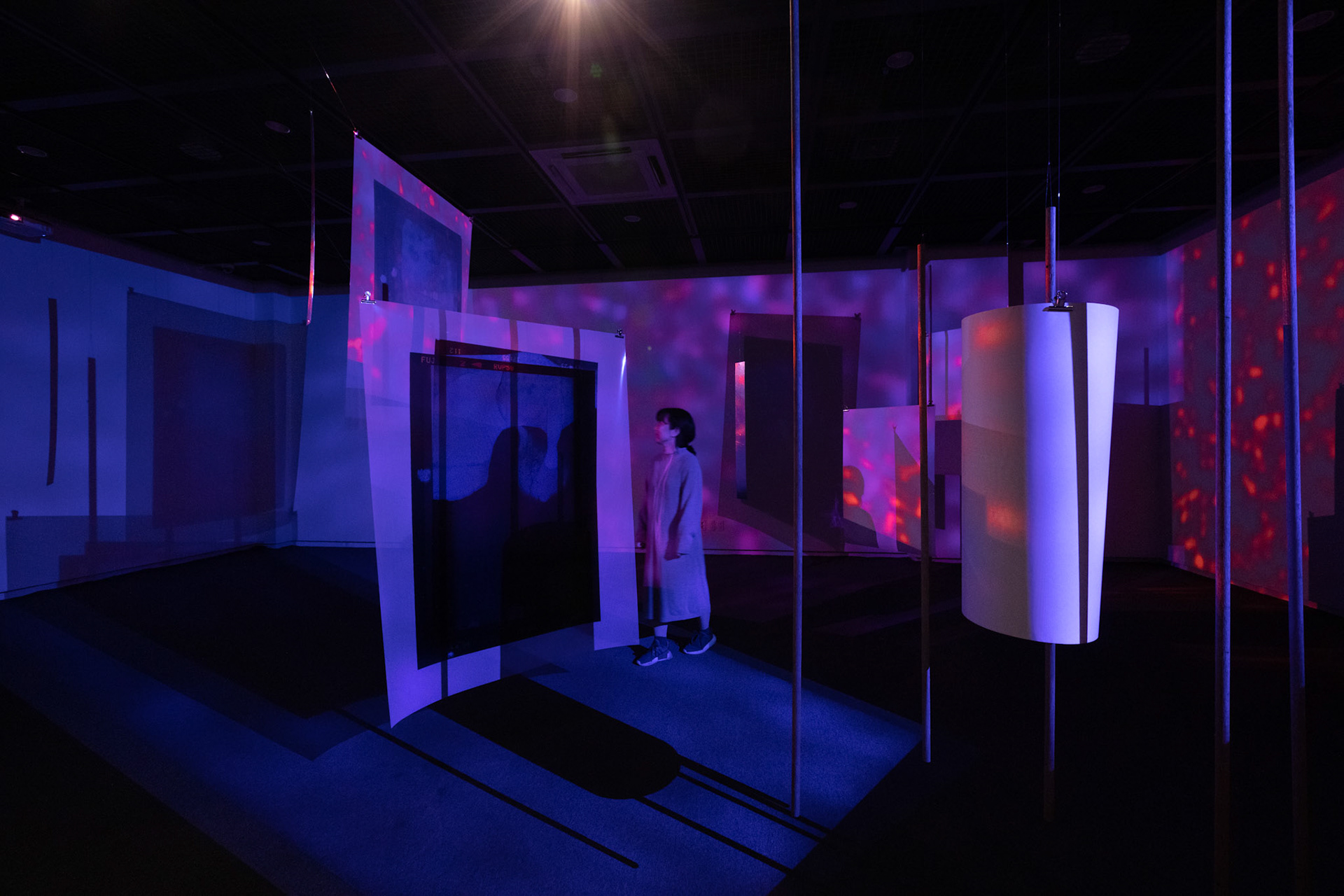

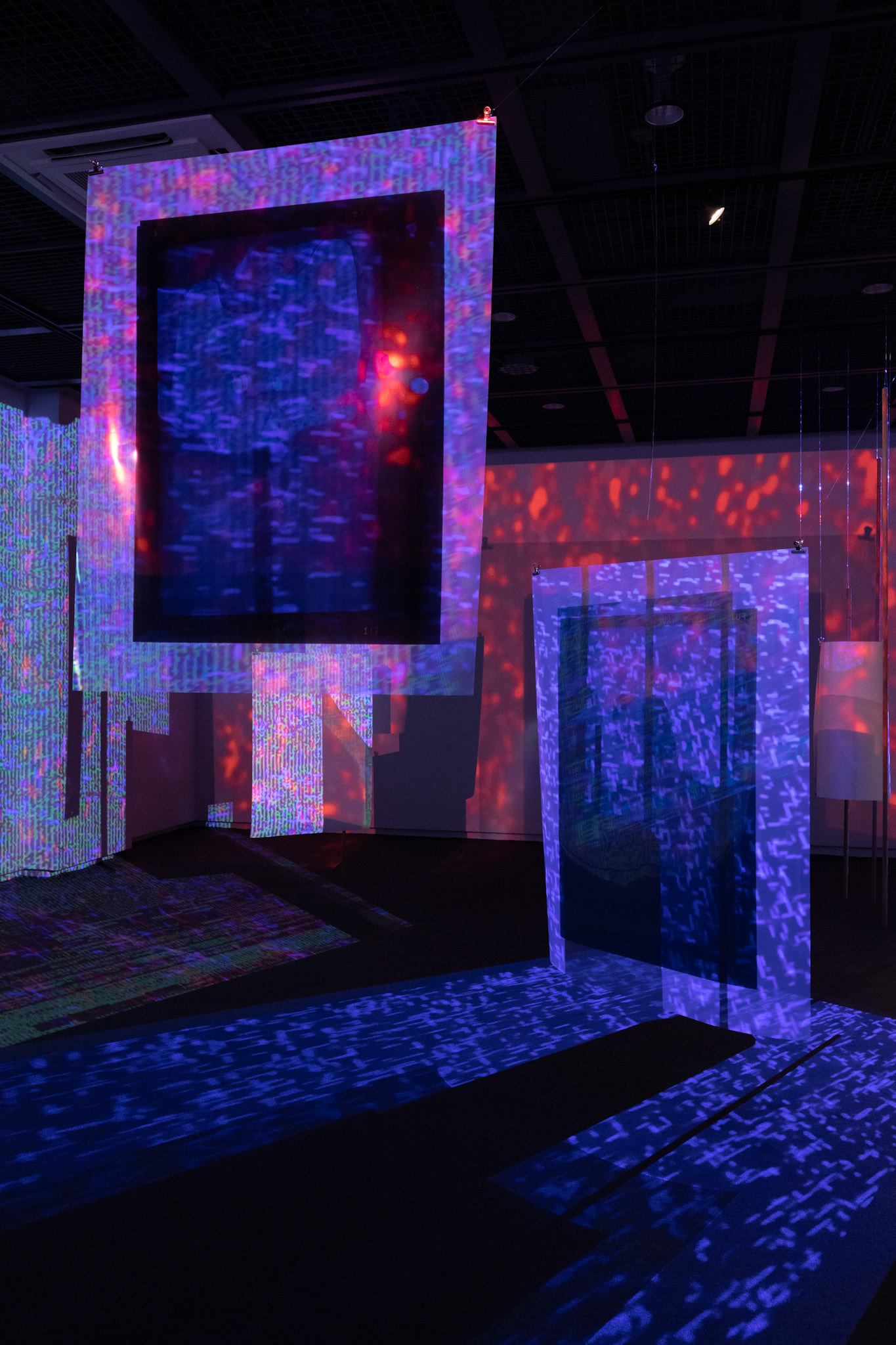

It scattered and turned red, 3CH Full HD Videos, No Sound, 05 : 00 min., Loop, 2020

It scattered and turned red, 3CH Full HD Videos, No Sound, 05 : 00 min., Loop, 2020

It scattered and turned red, 3CH Full HD Videos, No Sound, 05 : 00 min., Loop, 2020

It scattered and turned red, 3CH Full HD Videos, No Sound, 05 : 00 min., Loop, 2020

It scattered and turned red, 3CH Full HD Videos, No Sound, 05 : 00 min., Loop, 2020

It scattered and turned red, 3CH Full HD Videos, No Sound, 05 : 00 min., Loop, 2020

소환하고, 중첩시키고, 아우르며, 역행하는, 정교한 시간수리공

신보슬 (책임 큐레이터, 토탈 미술관)

짹깍짹깍

왜였는지 모른다. 박인성의 작품을 처음 마주했을 때,

조근조근 작품에 대한 설명을 들었을 때

짹각짹각 이 소리가 계속 머릿속을 맴돌았다.

짹깍짹각 시계소리가 들렸던 것은.

그에게서 시간을 이리저리 편집하는 시간수리공 같은 이미지를 떠올렸던 것은.

어쩌면 바람을 색깔로 바꾸고, 오래된 필름을 자르고 붙이고, 누군가를 인터뷰하는 등

하나의 형식으로 규정되지 않는 다양한 작업들이 마치 두 개의 시계바늘을 돌리는

서로 다른 크기와 모양의 톱니바퀴들을 닮았다는 느낌 때문이었는지 모르겠다.

박인성의 작품들을 한마디로 설명하기 쉽지 않다. 사용하는 매체의 종류도 다양할 뿐 아니라, 매체를 이해하고 사용하는 방식도 그만의 해석을 통해서 변화되기 때문이다. 때문에 그의 작품을 이해하기 위해서는 결과물로 제시되는 작품 못지않게 작품의 제작과정이 중요하다. 비록 관객에게는 그 과정이 명확하게 드러나 보이지 않을 수 있다 하더라도.

그의 초기작 <Picked Wind>(2013) 는 이러한 특성을 잘 보여준다. 바람의 속도를 측정하여 그것을 데이터 값으로 삼아 이미지와 사운드로 표현하는 이 작품의 경우 결과물인 영상설치만으로는 작품이 어떤 과정을 통해서 제작되었는지 알 수 없다. 그는 친절하게도 작업 진행과정에서 모아온 레퍼런스들을 함께 전시하여 관객이 작품이 어떻게 시작되었고, 어떤 고민의 과정을 거쳤으며, 어떤 기술들이 사용되었는지, 그리고 작품에서 들리는 사운드가 어떤 음악인지 악보까지도 관객들에게 공개한다. 누군가는 이러한 부수적인 자료들이 작품 자체에 집중하는데 방해가 된다고 할 수도 있고, 작품 설치에 있어서 공간이 어수선하게 보일 수 있다고 할 수도 있다. 하지만 관객의 입장에서 보면, 이러한 자료들이 작품에 한 걸음 더 다가가는데 도움이 되는 안내문이 될 수 있음은 분명하다. 굳이 이렇게까지 친절할 필요가 있느냐는 질문에 그는 대답했다.

“저는 미술계 전문가들을 위해서 작품을 만들지 않습니다. 일반 관객들을 위해서 만듭니다. 그러니 그들과 소통할 수 있는 최소한의 장치쯤은 있어야 한다고 생각합니다.:”

그의 말에 전적으로 동의하면서도, 다른 한편으로는 그 ‘최소한’을 어떻게 설정해야할지 여전히 고민스럽다. 그래서 이 글은 어쩌면 그의 작품 제작과정의 이야기를 불필요하게 길게 할지도 모르겠다.

작품의 제작과정에 대한 공유가 관객이 작품을 만나게 되는 지점에서 관객과 소통하는 중요한 하나의 축이라면, 작품 자체를 관통하는 주제는 무엇일까? 사진, 설치, 영상을 넘나드는 형식적인 편차 때문인지, 아니면 그가 주제를 다루는데 있어 명확한 언급을 꺼리기 때문인지 그 주제에 닿기가 쉽지만은 않았다. 그의 작품 설명을 녹음하고, 다시 듣고, 포트폴리오를 들춰보기를 몇 차례. 결국 ‘시간’이라는 개념에 맞닥뜨리게 되었다.

물론, 박인성은 본인의 작품을 시간에 대한 작품이라고 단언하지 않는다. 우연히 찾은 오래된 다큐멘터리 영화를 다시 편집한 작품 <Be Documentary>(2014)를 설명함에 있어 “연결된 시간, 깨어진 이미지”라는 단어를 쓰기는 하지만, 이는 ‘시간’자체에 대한 질문이라기보다는 ‘다큐멘터리’에 관한 일반적인 믿음에 관한 의구심이라는 편이 더 정확한 듯하다. 작업노트에서 박인성은 개입과 편집이 가장 적게 요구되며, 그로 인해 종종 다큐멘터리의 내용을 ‘사실’로 인식하게 되지만, 과연 다큐멘터리에서 이야기하는 사실의 실체는 무엇이냐고 묻는다. 결국 다큐멘터리 안에서 관객이 마주하는 것은 구축된 서사 구조, 즉 내러티브에 의해 ‘시간은 희생당하고, 관객은 인지 없이 “허구의 시간”을 만난다’(2014년 메모 中)고 이야기한다.

<Be documentary>가 예술적 개입 혹은 예술적 사실을 통해서 드러나는 허구의 시간에 대한 이야기를 하려했다면, 2015년 작품인 <Dreams>는 현재로 소환되는 과거의 시간에 대한 이야기라 할 수 있다. 나이가 지긋한 어른들에게 그들의 어린 시절 꿈(어떤 사람이 되고 싶었는지)에 대해서 묻는다. 참가자는 질문에 대답하는 과정에서 두 가지 규칙을 제시한다. 첫째 ‘내가 어렸을 적에는..’이라고 시작하면 안 되고, 둘째 과거형으로 말해서는 안 된다. 대답은 현재형 혹은 미래형으로만 이루어져야 한다. 언뜻 단순해 보이지만, 이야기가 전개될수록 그 단순한 규칙들이 이야기를 자꾸만 가로막는다. 참가자는 끊임없이 과거의 나를 현재에 마주하고, 과거의 내가 꿈꾸었던 미래의 나와 현재의 나를 동시에 만나게 된다. 시간은 과거에서 현재를 거쳐 미래로 흐른다고 했던가. 하지만, 박인성의 작업에서 보여주는 시간들은 그렇지 않다. 그렇게 롱 테이크로 찍은 후 이렇다 할 편집도 없이 거의 그대로 보여주는 인터뷰 영상은 현재를 기록하고 있는 동시에 계속해서 과거를 소환하고, 과거의 미래와 현재가 뒤섞이면서 시간들이 동시에 공존하고 교차하면서‘지금들’이라는 순간에서 만나게 된다.

초기 <Picked Wind>의 연장이라 할 수 있는 <Tone Color>(2016)는 제목에서 짐작할 수 있듯‘색’에 대한 관심이 본격화되는 시기의 작품이라 할 수 있다. 색에 대한 그의 관심은 외국에서 이방인으로 살면서 종종 겪게 되는 피부색에 의한 선입견으로부터 비롯되었다. 그는 이를 ‘첫인상’이라는 단어로 설명했는데, 사람과 사람이 만나는 상황에서 피부색이라는 것이 주는 인상이 강렬한 것인지 아니면 사람의 아우라가 중요한 것인지에 대한 궁금증을 시/청각적으로 풀어내 보고 싶었다고 했다.

이 작품을 위해 직접 모델을 섭외하여 그들의 일상 공간으로 찾아가 가장 익숙한 곳에서 그리고 알몸으로 빛을 받도록 하고 촬영했다. 그날의 날씨, 상황에 따라서 달라지는 빛을 받는 피부색의 변화를 촬영하고, 초당 25프레임의 영상에 맞춰 1초당 25개의 숫자를 채취 할 수 있는 알고리즘을 구성한 후 이를 기반으로 취합된 데이터를 바탕으로 음악을 만들었다. 그리고 데이터 수치에 따라 악기값을 설정하였는데, 태닝을 한 백인의 경우 미들톤의 피아노, 전신에 타투를 가진 한국인 모델은 색의 변화가 적고 어두워서 첼로를, 또다른 한국인 모델은 피부톤이 밝은 편이었지만, 역시 몸에 타투가 있어 색의 변화가 크게 눈에 듸지 않아 바이올린을 할당했다. 이렇게 각 영상마다 고유한 음악을 완성하였으며, 3개의 모니터가 삼각구도로 배치된 3 채널 영상설치를 통해 보여주었다.

흥미롭게도 <Tone Color>은 ‘색’이라는 지극히 객관적인 듯한 주제에 닿아 있으면서도 빛에 따라 변화하는 피부색이라는 주제로 넘어가면서 주관적인 성격이 가미되면서 묘한 이중성을 보여준다. 박인성은 이것이 색이라는 것이 가진 특징이라고 이야기한다. 사람들은 객관적으로 어떤 색이 존재하는 것처럼 이야기하지만, 각자 인지하는 색은 다르다고 이야기하면서, 색이 가지고 있는 이런 특성에 주목한다. 색을 둘러싼 이러한 이중적 혹은 다른 성격의 공존은 마치 <Dreams>가 현재시점에서 단순한 두 가지 규칙을 통해서 과거, 현재, 미래를 동시에 소환하고, 그로 인해 다양한 시간대의 공존을 불러오는 것과 유사하다. <Dreams>가 시간대의 소환이었다면, <Tone Color>는 색이라는 키워드를 전면에 내세우지만, 여기에 빛과 음악이 좀 더 적극적으로 개입되어 시간의 흐름을 시각화시킨다. 그래서 전작들에 비해서 시간이라는 주제가 명확하게 드러나지는 않지만, 좀 더 복잡하고 다양한 구조 안에서 드러나는 시간의 흐름은 확실히 이전 작업보다 세련되고, 아름다워졌다.

그렇다면 사진에서 그가 보여주는 시간은 어떤 모습일까? 사건의 순간, 현상의 순간을 담은 사진 속에서 시간은 멈춘다. 그래서 우리는 종종 사진이 대상이나 사건을 ‘포착’한다는 표현을 쓴다. 흥미로운 것은 박인성의 사진은 시간을 가두고 포착하는 사진이라기보다는 시선의 확장을 통해 시간의 흐름을 ‘감지’하게 하는 사진이라는 점이다. 처음 작업실에서 작품을 마주했을 때, 기하학적 추상 같은 작업인가보다 했다. 하지만 작은 소품에서도 쉽사리 시선을 뗄 수 없었던 것은 사진 이미지가 너무 새롭거나 신선했기 때문은 아니었다. 도형들이 만들어낸 구도에서 색감으로 레이어 된 공간으로 시선이 끊임없이 이동하면서 자연스러운 흐름을 이어갔기 때문이었다. 이처럼 정적인 이미지 안에서 은밀하게 시선의 이동을 촉발하고, 시간의 흐름과 공간의 확장을 경험하게 되는 이유는 그가 다루고 있는 ‘색’이라는 것이 종이나 천에 고착화된 피그먼트 색이 아닌 빛을 머금고 한없이 인지적으로 확장되는 색, 시간을 담고 있는 색이었기 때문이었던 것 같다.

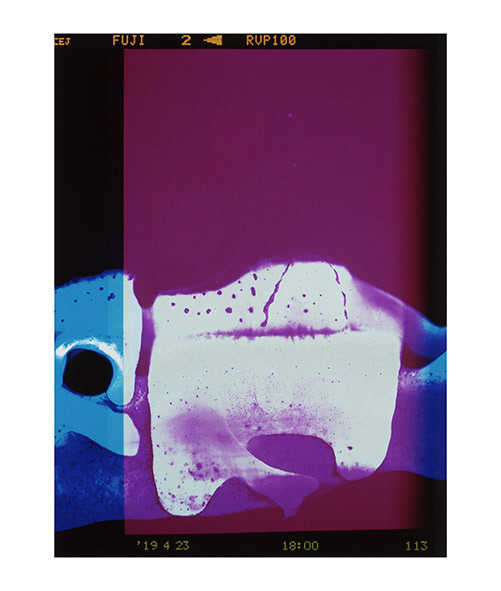

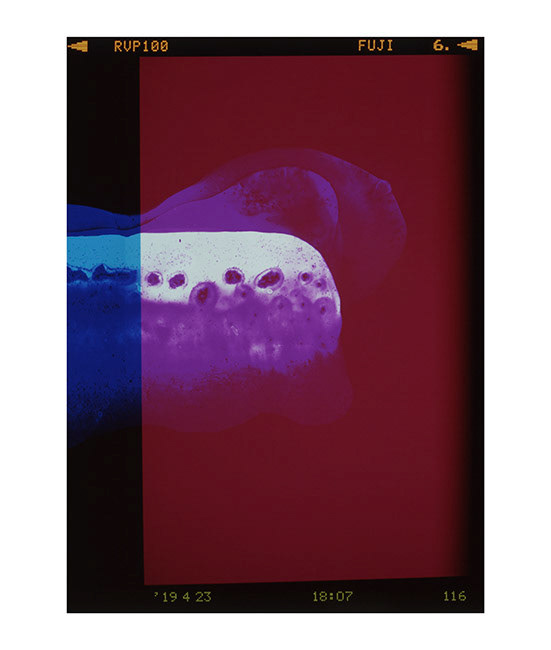

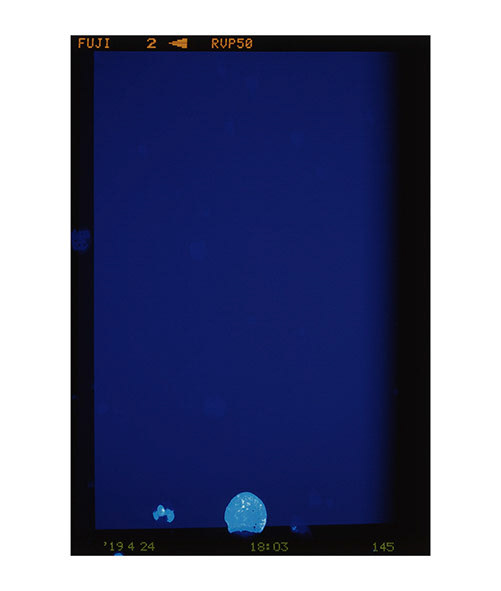

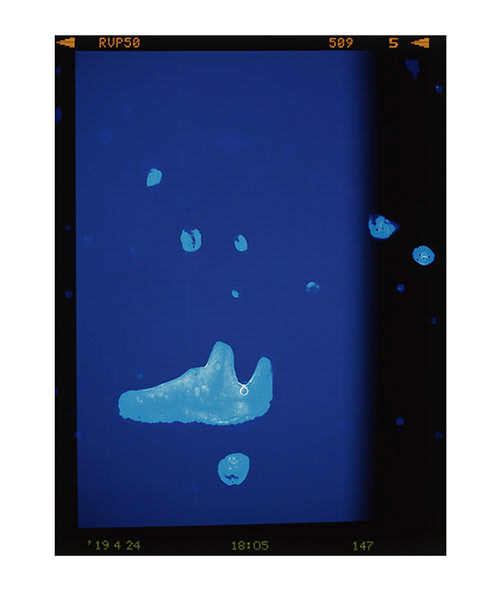

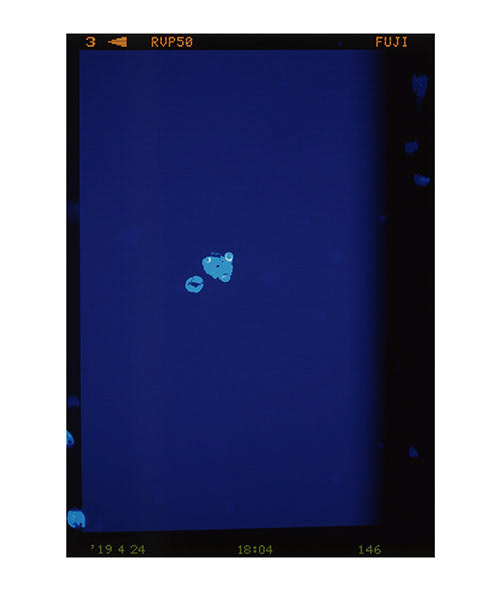

이번 전시에 소개된 사진 작업들에서도 이런 특징은 잘 드러난다. 푸른 빛 바탕에 아주 다른 강도의 푸른빛으로 중첩되어 만들어지는 사각형. 역시 검은색을 한껏 머금은 초록빛. 그리고 그 빛을 머금은 사각형과 검은 사각면 사이의 그리드. 사진이 대상을 찍는 것이라면, 지금 박인성의 film 시리즈는 무엇을 찍은 것일까 궁금해졌다. 그가 찍은 것은 조각난 필름일까? 아니면 조각난 필름들을 이리저리 흐트러트리고 다시 재구성하면서 만들어낸 구성일까? 아니면 그 구성을 통해서 드러내는 색감일까? 그 모든 것일 수도, 아닐 수도 있지 않을까? 뭐라 꼬집어 단정할 수는 없지만, 아무튼 그의 작품은 작품 속 이미지를 하염없이 바라보게 하는 매력이 있다. 이렇다 할 클라이막스나 감동적인 스토리가 없음에도 불구하고.

그렇다면 하염없이 이미지를 바라보게 하는 것은 무엇일까? 또 다시 정답 없는 궁금증이 생겨났다. 조각난 필름을 찍고 그것을 드러내려 했다면, 아마 관객은 대상을 인지하는데 집중했을 것이고, 그것을 인지하는 순간 이미지에 대한 관심은 사라지게 된다. 그래서 사진작품들은 종종 본래의 대상을 더욱 아름답게 보여주거나 혹은 새로운 방식으로 쉽게 대상 자체를 인지하지 못하게 하는 작전을 쓰곤 한다. 하지만, 박인성의 작업은 조각난 필름을 아름답게 보여주는 것도, 빛으로 드러나는 색감에 집중하는 것도 아니다. 오히려 필름이라는 물리적인 대상과 그것을 통과해 나가는 빛, 그리고 빛에 의해 드러나는 색과 같이 이질적인 것들이 어우러져 이미지를 만들어낸다.

그리고 여기에서 그가 이야기했던 최소한의 친절함이 또 드러난다. 그냥 잘라버렸으면 이미지를 만든 방식과 재료에 대해 신비감을 남겼을 수도 있을 텐데, 친절하게도 필름 가장자리 표식이나 필름 상표를 그대로 드러내 보여준다. 그래서 세심하게 작품을 본 관객이라면, 작품 속 이미지가 카메라 필름을 통해 만들어진 것임을 알아차릴 수 있게 된다. 그리고 이미지가 필름이라는 것을 통해 만들어졌다는 것을 인지하는 순간 단순한 평면이었던 이미지는 필름이라는 물성이 겹쳐짐으로 만들어낸 레이어로 전환된다. 그렇게 한 곳에 고정되었던 시선이 뒤로 빠져가면서 또 다른 공간감이 만들어진다.

박인성의 작업은 그렇게 사건/대상이 아닌 시간을 시각화한다. 대상이 아닌 색을 필름에 얹어 공간의 겹침을 만들어내고, 공간의 겹침은 다시 시간의 레이어를 만들어낸다. 박인성의 사진 속 시간은 그렇게 레이어 된 공간 사이에서 빛으로 퍼지는 색을 통해 드러난다.

째깍째깍.

박인성의 작업을 되돌아보는 동안, 여전히 이 소리가 머릿속에 맴을 돌았다.

영상, 사진, 설치/ 색, 첫인상, 빛 / 다큐멘테이션, 인터뷰/ 사실, 사건, 현상

서로 다른 매체와 형식과 주제를 넘나들지만 결국은 시간이라는 핵심 키워드를 축으로 돌아가고 있다고 한다면 너무 단순화시킨 것일까?

그럼에도 불구하고, 그의 작품들에서 서로 다르게 시각화된 시간들을 본다.

그에게서 시간수리공의 모습을 본다.

여기에서 시간수리공은 고장 난 시간을 고치는 수리공이 아니다.

사진에서도 영상에서도 과거, 현재, 미래가 무작위로 소환되고 편집되고 어우러지는 시간들

개개의 작품들을 마치 서로 다른 톱니바퀴를 꿰맞추듯 다양하게 구성되는 시간들

그렇게 일상에서 볼 수 없는 혹은 스쳐 보내는 시간들을 만들어 내는 수리공이다.

시간수리공이다.

film 048, 2020, Digital C-Print on Transparent Paper, 53 x 45cm

film 049, 2020, Digital C-Print on Transparent Paper, 53 x 45cm

film 050, 2020, Digital C-Print on Transparent Paper, 53 x 45cm

film 051, 2020, Digital C-Print on Transparent Paper, 53 x 45cm

film 052, 2020, Digital C-Print on Transparent Paper, 53 x 45cm

film 053, 2020, Digital C-Print on Transparent Paper, 53 x 45cm

film 054, 2020, Digital C-Print on Transparent Paper, 53 x 45cm

film 055, 2020, Digital C-Print on Transparent Paper, 53 x 45cm

film 056, 2020, Digital C-Print on Transparent Paper, 53 x 45cm

film 057, 2020, Digital C-Print on Transparent Paper, 53 x 45cm

Installation View

Installation View

Installation View

Installation View

Installation View

The Meticulous Time Repairman: Summoning, Overlapping, Combining, and Regressing

Nathalie Boseul Shin

(Chief Curator, Total Museum of Contemporary Art)

Tick, tick.

I’m not sure why, but when I first stood before the artwork of Inseong Park and heard it quietly explained,

this “tick, tick” sound kept going around in my heard. I could hear the ticking of a clock.

The image I got from him was something like a time repairman, editing time here and there.

Perhaps this came from the sense that his different works, undefinable as they are in terms of any one form –

changing wind into colors, cutting and pasting old film, interviewing people –

seemed similar to cogwheels of different shapes and sizes turning two clock hands.

Inseong Park’s works are not easy to explain in simple terms. Not only does he employ a wide range of media, but the ways in which he understands and uses media also transform through his own unique analyses. In that sense, the process behind the production of his work is as important in understanding it as the finished product presented before us – even if that process might not be clearly visible to the viewer.

His early work Picked Wind (2013) offers an excellent illustration of this. Using wind speed measurements to provide data that are then expressed in images and sound, the resulting video installation by itself offers no indication of the process behind its production. Generously enough, he also shares the references assembled during his working process, letting viewers see how the work began, what sort of questioning process he went through, what techniques were used, the kind of music in the sounds heard in the work, and even the score. Some might argue that such incidental data get in the way of concentrating on the work itself, or that the space appears disordered as an installation. From the viewer’s standpoint, however, this information certainly can offer an aid in approaching the work more closely. When asked whether he really needed to be so generous, Park replied as follows:

“I don’t make artwork for art world experts. I make it for ordinary viewers. And so I think it ought to have at least some kind of device for communicating with them.”

I do agree with him completely, but I also have some lingering questions about how that “at least” should be decided. As a result, this essay may be needlessly lengthy in its discussion of his working process.

If sharing the work’s production process represents an important aspect of communication with the viewer encountering the artwork, what theme could be said to run through the work itself? That topic was not so easy to pinpoint – perhaps because of the formal differences when alternating among media of photography, installation, and video, or the artist’s own reluctance to make clear statements when dealing with theme. I recorded his explanations of his artwork, listened again, went through his portfolio several times – and ultimately I came across the concept of “time.”

To be sure, Inseong Park himself does not declare his own work to be about time. He has used the terms “connected time, broken image” in explaining his work Be Documentary (2014), which was produced by re-editing old documentary films he had come across. But rather than interrogating time per se, it seems more accurate to say that he is skeptical of general beliefs regarding the “documentary” medium. In his artist’s notes, Park notes that the documentary format requires the least intervention and editing, and that the resulting content is consequently seen often as “factual” – but he then questions the true nature of the facts related in documentary works. As a result of the narrative structure established within documentaries, he explained in a 2014 memo, “time is sacrificed, and the viewer encounters ‘false time’ without being cognizant of it.”

If Be Documentary attempted to address the false time revealed through artistic intervention or artistic truth, then Park’s 2015 work Dreams could be seen as about past time summoned into the present. Park asks people who are aging what they dreamed about when they were children (what kind of people they wanted to be). For the response process, he states two rules: they should not start their answers with “when I was young,” and their answers should be only in the present or future tense, not the past. It seems simple, but as the answers go on, those simple rules keep getting in the way of the story. The participants are constantly encountering their past self in the present, and meeting simultaneously the future self they dreamed of in the past and the present self. Isn’t time said to flow from past to present and on to the future? Yet this is not the case with the times seen in Inseong Park’s work. Filmed in long takes, his interview footage is shown more or less intact, without any editing to speak of. As it records the present, it keeps summoning the past, and as the past’s future and the present mix together, different times coexist and intersect, meeting each other in moments of “nows.”

As its title suggests, Tone Color (2016), which could be seen as a continuation of the early Picked Wind, may be a product of the period during which the artist’s interest in color truly flowered. Park’s interest in color stems from prejudices due to skin color that he often encountered while living as an alien overseas. He has described this in terms of a “first impression,” explaining that he wanted to express in visual/acoustic terms his curiosity as to whether the impression conveyed by skin color in meetings between one person and other is truly powerful, or if a person’s aura is important.

For this work, Park contacted models directly, visiting their day-to-day spaces and filming them so that they were lit, naked, in the most familiar of spaces. He developed an algorithm to gather 25 figures per second on changes in the skin color under lighting, based on changes in the weather and conditions that day – a number chosen to match a 25 frame-per-second video. The data thus assembled were used as a basis to compose music. Instrument values were also chosen according to the data values: a middle tone piano for a Caucasian with a tan, a cello for a Korean model with full body tattoos (due to the darkness and few color changes), and a violin for another foreign model who had a light skin tone but did not exhibit much in the way of color changes because of tattoos. Music was created for each video and presented in a three-channel video installation with three monitors organized in a triangular arrangement.

Interestingly, even as it touches upon the seemingly quite objective theme of “color,” Tone Color exhibits an odd duality, assuming a subjective character as it proceeds to the theme of skin color changing according to lighting conditions. Park has referred to this as a characteristic of color, noting that while it seems to exist objectively, the colors perceived by each person are actually different. This coexistence of dual or differing natures surrounding color is similar to the way that Dreams, with its two simple present-tense rules, simultaneously summoned the past, present, and future, thus invoking a coexistence of different times. If Dreams was about summoning different times, then Tone Color visualizes the flow of time, with the light and music intervening more actively as the color appears in the foreground. The theme of “time” is not emphasized as much as in previous works, but the flows of time revealed within more complex and varied structures were certainly more sophisticated and beautiful than in Park’s past work.

How does it appear, this time that Park presents in his photographs? In images that capture moments from events or phenomena, time is stopped; this is why we often talk about “capturing” a photograph. The interesting thing about Park’s photographs is that rather than trapping and seizing time, they “detect” flows of time through expansions of perspective. When I first encountered his work in the studio, it seemed like some kind of geometric abstraction piece. But the reason I could not tear my eyes from even the small props was not because the photographic image was that new or fresh. It was because of the constant movement and natural flow of the gaze to a space layered in terms of color sense within the composition formed by the figures. Perhaps the chief characteristic was that the colors he used were not pigments affixed to paper or canvas, but colors that harbored light and underwent a cognitive expansion – colors that “contained” time.

That characteristic is clearly in evidence in the photographic works shown in this exhibition. Rectangles formed by the overlaying of very different intensities of blue on a blue background. Greens that are richly filled with black. And the grids between the light-harboring rectangles and the black rectangular plane. I found myself asking: if photography is about capturing subjects, what was Inseong Park now capturing with his film series? Were his pictures of fragmented film? Or was it a composition produced by strewing fragmented film about and then piecing it back together? Perhaps it was the color sense revealed through that composition? Could be it all of these things or none of them? The fascinating thing was that while I cannot exactly put my finger on why, I find myself endlessly staring at the images in the work – even though there is no “climax” or emotional story to speak of.

What is it, then, to stare endlessly at an image? Here arose another question without a definite answer. If the artist had attempted to capture and show fragmented film, perhaps the viewers would have focused on perceiving the object, and their interest in the image would evaporate the moment they did. For that reason, the works of photography sometimes employ strategies to make the original object appear more beautiful, or incorporate new methods that make the object difficult to recognize. But Inseong Park’s work is not about showing fragmented film in beautiful ways; it is not focused on the color sense revealed through light. Instead, the image is formed as different things – the physical subject (film), the light passing through it, and the colors revealed through that light – come together. In his generosity, the artist shows us the label on the film’s edge and the brand name. This may be the kind of “at least some kind of device” he has referred to. The attentive viewer can detect that the image in the work was created with camera film. At the same time, images shown only in two dimensions form layers with the overlapping of film, while a different spatial sense is created as the once-fixed perspective recedes. In these ways, Inseong Park’s artwork captures moments in time rather than incidents, placing color on film rather than objects – and thus creates layers of life through the overlapping of spaces. Time within his photographs is revealed through color as it spreads with the light amid the layers of space.

Tick, tock.

The sound continued in my head as I reflected on Inseong Park’s artwork.

The artist works with different media, forms, and themes –

video, photography, installation/color, first impressions light/documentation, interviews/truth, incidents, and phenomena.

Would it be too simplistic to say in the final analysis that it all operates around the keyword of “time”? Yet in his works,

I see different times visualized in different ways.

In him, I see a “time repairman.” A time repairman, of course, is not someone who fixes broken time.

He is someone who crafts different times: times in which past, present, and future are summoned, edited,

and combined at random in both photography and media.

Times configured in different ways in individual artwork, like different cogwheels becoming interlocked.

Times we cannot see in daily life; times that flash past us. And so he remains a time repairman.